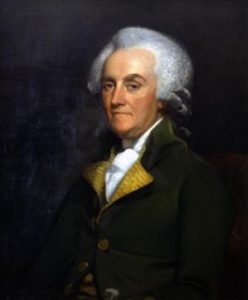

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin Biography

Early Years

Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, in what was then known as the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

His father, Josiah Franklin, emigrated from England in 1682. He had 7 children with his first wife, when she died he married Abiah Folger and had 10 more children, a total of 17. Benjamin was the was the 15th and youngest son. His mother, Abiah Franklin (Folger) was the daughter of Peter Folger, one of the first settlers of New England.

Franklin learned to read at an early age, and despite his success at the Boston Latin School, he stopped his formal schooling at 10 to work full-time in his cash-strapped father’s candle and soap shop. The job of dipping wax and cutting wicks didn’t last long for him and he wanted more.

Additional Resources:

Web Sites:

Books:

Ben Becomes a Printer

Franklin wanted to go to the sea but his father didn’t want that to happen so he convinced James (Benjamin’s brother) to sign Benjamin as his printer’s apprentice. He signed a nine year apprenticeship contract at 12 years old to work as a printer’s apprentice.

James put Benjamin to work setting type, cleaning up, and making deliveries, just like any other apprentice. In 1721 James decided to start a newspaper, the New England Courant. The Courant reported on local news with smart reporting and reader’s contributions. In 1723, the Massachusetts legislature decided that the Courant had mocked religion and the government and should be punished. They put James in jail and passed an order that “James Franklin should no longer print the paper.”

James came up with a plan to keep the paper running by publishing the paper under Benjamin’s name. So at 17 years old Benjamin became the publisher of the Courant. James cancelled Bejamin’s apprentice contract but made Benjamin sign a new secret apprenticeship agreement.

James came up with a plan to keep the paper running by publishing the paper under Benjamin’s name. So at 17 years old Benjamin became the publisher of the Courant. James cancelled Bejamin’s apprentice contract but made Benjamin sign a new secret apprenticeship agreement.

Benjamin guessed that James would not want to reveal the secret apprenticeship agreement and so he took advantage of the situation. Benjamin ran away to try to make it on his own.

Ben Goes to Philadelphia and London

In September 1723 Benjamin runs away to New York and then moves to Philadelphia. He began working as a journeyman printer at the printing business of James Keimer. Gov. Keith of Pennsylvania encouraged Franklin to start his own printing business and promised to provide capital. In 1724, at the age of 18, he was going to by printing equipment to open up his own print shop and possibly start a newspaper. Sir William Keith, the Royal Governor of Pennsylvania, had promised to pay for equipment if Ben would go to London to pick it out and bring it back. Governor Keith promised to send a letter of credit (which is a promise to pay for something) ahead of Ben so he would have the money when he got there. Unfortunately, when Ben arrived in London on December 24, 1724, he realized that Governor Keith had not followed through on his part and had no intention of paying for the printing equipment.

This left Ben stranded in England at the age of 18. Ben went straight to the printing house of Samuel Palmer, who was a famous and prestigious British printer, and got a job within a few days. Ben stayed in London for about a year and a half, working to live and earn the money to pay for the trip back to Philadelphia. During that time he also worked for another famous London printer, James Watts.

Ben finally left London on July 22, 1726 with a merchant from Philadelphia, Thomas Denham, a shopkeeper for whom Ben worked when they returned. They arrived back in Philadelphia on October 11, 1726.

Benjamin creates the Junto (1727)

In the fall of 1727 Benjamin Franklin (21 years old) and a group of friends founded the Junto Club also known as the Leather Apron Club. The 12 members were tradesmen and artisans who met Friday evenings to discuss issues of morals, politics or natural philosophy. The club lasted 38 years. Franklin proposed that the group be formed of “ingenious men –a physician, a mathematician, a geographer, a natural philosopher, a botanist, a chemist, and a mechanician (engineer)”.[1]

In the fall of 1727 Benjamin Franklin (21 years old) and a group of friends founded the Junto Club also known as the Leather Apron Club. The 12 members were tradesmen and artisans who met Friday evenings to discuss issues of morals, politics or natural philosophy. The club lasted 38 years. Franklin proposed that the group be formed of “ingenious men –a physician, a mathematician, a geographer, a natural philosopher, a botanist, a chemist, and a mechanician (engineer)”.[1]

Benjamin's son William is born (1727 or 1728)

Benjamin has an affair with a woman that results in an illegitimate son named William. Benjamin would never tell who was William’s mother. Documentation of William’s true birth date would never be found.

William would be raised by Benjamin and Debroh Reed and he would use Benjamin’s fame and connections to get him jobs and powerful appointments throughout his life. Benjamin and William would have a very turbulent relationship and would would never see eye to eye on political or phisolphical areas. In 1763, using Ben’s fame, William would become Royal Governor of New Jersey and later would side with England during the Revolutionary War which caused an irreversible split between father and son. [2]

The Pennsylvania Gazette (1729)

On October 2, 1729 Benjamin Franklin and his partner Hugh Meredith seized the opportunity to purchase the Pennsylvania Gazette from Samuel Keimer. Keimer sold his publication because he was greatly indebted due to other business ventures.[3]

The two partners bought the struggling paper and quickly turned it into a well-written, well-edited, and well-printed newspaper. In format, Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette was like other colonial American newspapers. The emphasis was on news, not literary or political essays, and most of that news was copied from European papers. But Franklin had a knack for selecting, editing, and rewriting. And, if his autobiography is to be believed, the Gazette “prov’d in a few Years extreamly profitable.”[4]

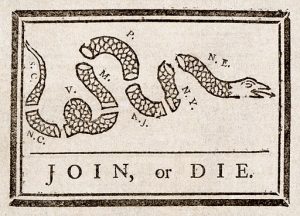

His newspaper soon became the most successful in the colonies. This newspaper, among other firsts, would print the first political cartoon in America, “Join, or Die,” authored by Franklin himself. The newspaper gave a first hand view of the time before, during and after the American Revolution. Over the 71 years of the publication there were thousands of editorials, news reports, articles and advertisements. It was the pre-eminent newspaper of it’s time and thus was very influential and part of the American culture. The Pennsylvania Gazette ceased publication in 1800, ten years after Franklin’s death. Some claim the publication became the Saturday Evening Post; though it can not be substantiated.[5]

His newspaper soon became the most successful in the colonies. This newspaper, among other firsts, would print the first political cartoon in America, “Join, or Die,” authored by Franklin himself. The newspaper gave a first hand view of the time before, during and after the American Revolution. Over the 71 years of the publication there were thousands of editorials, news reports, articles and advertisements. It was the pre-eminent newspaper of it’s time and thus was very influential and part of the American culture. The Pennsylvania Gazette ceased publication in 1800, ten years after Franklin’s death. Some claim the publication became the Saturday Evening Post; though it can not be substantiated.[5]

The Library Company (1731)

On September 1, 1730, the Benjamin married Deborah Read as a common law wife. Deborah’s previous husband, John Rogers, was claimed to have died in the British West Indies; even though a body was never found. At that time, the law in the Province of Pennsylvania would not grant a divorce on the grounds of desertion. She could neither claim to be a widow, as there was no proof that Rogers was dead.[6] Common law marriages was legal in that jurisdiction so that is what they decided to do.

Deborah assisted in the business by folding and stitching pamphlets, tending shop, purchasing old linen rags for paper makers. He found her a “good and faithful helpmate”. Around the time they married Franklin took custody of an illegitimate child, William. The name of the mother remains a mystery. The couple had two children. The first was Francis Folger Franklin born October 1732. The second, Sarah Franklin born in 1743. In 1736 Francis, who was 4 years old, died from small pox. He had not been inoculated. Inoculation had proven successful after the 1721 outbreak in Boston when 5,889 Bostonians had smallpox, and 844 died of it.[7]

The Library Company (1731)

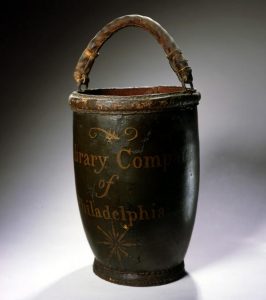

On July 1, 1731, Franklin and a number of his fellow members among the Junto drew up articles of agreement to found a library, The Library Company, for they had discovered that their far-ranging conversations on intellectual and political themes floundered at times on a point of fact that might be found in a decent library.[8]

The idea to create a lending library started during Junto Club gatherings where each member would bring books to share with others and consult during debates but bringing books back and forth became cumbersome. It was agreed by the members to keep the books in the meeting room so that all members would benefit from them. It was also of great benefit to borrow a book and bring it home to read, therefore the idea of starting a public subscription library. Franklin’s goal was to benefit the common people who otherwise would not have access to books.[9]

Sets up the first Francise (1731)

In 1731 Franklin drew up a six-year contract that allowed Thomas Whitmarsh to establish himself as a printer in South Carolina. Franklin purchased the printing press and types in return for one-third of the profits.[10] Whitmarsh died two years later and Franklin appointed his journeyman Lewis Timothee to run the shop. Timothee died soon after, his son was underage and unable to run the business so his wife Elizabeth Timothee took over and became the first woman franchisee. During the time the Founding Father was in the printing business he had two female franchisees, the second one was his sister-in-law, Ann Smith Franklin who went into partnership with him in 1762.[11]

Poor Richard's Almanack (1732)

Franklin published the first Poor Richard’s Almanack on December 28, 1732 and was published each year for 25 years. It was one of the most popular publications of that time sellling over 10,000 copies each year. The Almanack was a big economic success for him and increased his fame even more.

The Almanack contained the calendar, weather, poems, sayings and astronomical and astrological information that a typical almanac of the period would contain. Franklin also included the occasional mathematical exercise, and the Almanack from 1750 features an early example of demographics. It is chiefly remembered, however, for being a repository of Franklin’s aphorisms and proverbs, many of which live on in American English.

Please see an exhaustive list of proverbs and aphorisms from Poor Richard’s Almanack at poorrichards.net/. Some of the most famous are: “Haste makes waste”, “No gains without pains”, “Lost time is never found again” and “Well done is better than well said”

Chosen Clerk of the General Assembly (1736)

In 1936 he was chosen to be the Clerk of the General Assembly in Pennsylvania’s colonial government, he served as the Clerk of the from 1736-1750. [12]

Forms the Union Fire Company of Philadelphia. (1736)

After visiting Boston, Franklin noticed that Philadelphia residents were not as prepared to fight fires as was Boston. He would discuss this with the Junto as well as published several articles in the paper discussing the issue and asking for suggestions.

Goodwill and amateur firefighters were not enough, though. Franklin suggested a “Club or Society of active Men belonging to each Fire Engine; whose Business is to attend all Fires with it whenever they happen.” With Franklin’s urging, a group of thirty men came together to form the Union Fire Company on December 7, 1736. Their equipment included “leather buckets, with strong bags and baskets (for packing and transporting goods), which were to be brought to every fire. The new Union Fire Company met monthly to talk about fire prevention and fire-fighting methods. To help combat fires homeowners were mandated to have leather fire-fighting buckets in their houses. For more details about Franklin’s Union Fire Company Union Fire Company Click Here [13]

Appointed Postmaster of Philadelphia (1737)

In 1937 he was appointed to be the Postmaster of Philadelphia. In his autobiography, Franklin wrote that he accepted the post readily, “and found it of great advantage; for, tho’ the salary was small, it facilitated the correspondence that improv’d my newspaper, increas’d the number demanded, as well as the advertisements to be inserted, so that it came to afford me a considerable income.”

As a publisher in Philadelphia, Franklin had suffered under the previous postmaster, who like many colonial postmasters was also a newspaper publisher. Publishers vied for postmaster jobs, knowing they would get the news first, could mail their newspapers for free and even refuse competing papers access to the mails. [14]

Invents the Franklin Stove (1742)

In 1742, Benjamin invented the original version of the Pennsylvania Fireplace, which eventually came to be known as the Franklin Stove. The original Pennsylvania Fireplace was a freestanding cast-iron fireplace, and it was designed to be inserted into an existing fireplace. Ben’s design was successful in that it made fireplaces safer and more efficient. There was a major flaw, however. Ben designed it so that smoke came out from the bottom of the fireplace. The stove was unable to work properly because smoke rises. In spite of the fact that improvements were obviously needed, the invention was being widely used. Benjamin was offered a patent on the Franklin Stove. Ben refused, however, to patent the popular invention. He selflessly wanted the design to benefit others, and he wanted other inventors to freely improve on his work. In his writings, Benjamin said that he considered providing the stoves as a service to be better than any financial rewards he may have received.

In 1742, Benjamin invented the original version of the Pennsylvania Fireplace, which eventually came to be known as the Franklin Stove. The original Pennsylvania Fireplace was a freestanding cast-iron fireplace, and it was designed to be inserted into an existing fireplace. Ben’s design was successful in that it made fireplaces safer and more efficient. There was a major flaw, however. Ben designed it so that smoke came out from the bottom of the fireplace. The stove was unable to work properly because smoke rises. In spite of the fact that improvements were obviously needed, the invention was being widely used. Benjamin was offered a patent on the Franklin Stove. Ben refused, however, to patent the popular invention. He selflessly wanted the design to benefit others, and he wanted other inventors to freely improve on his work. In his writings, Benjamin said that he considered providing the stoves as a service to be better than any financial rewards he may have received.

Benjamin’s design was improved upon by others, including David R. Rittenhouse. Rittenhouse added an L-shaped chimney, and he called his improved appliance a Rittenhouse Stove in the late 1780’s. But his design was known then as the Franklin Stove, and it still is today.

As a publisher in Philadelphia, Franklin had suffered under the previous postmaster, who like many colonial postmasters was also a newspaper publisher. Publishers vied for postmaster jobs, knowing they would get the news first, could mail their newspapers for free and even refuse competing papers access to the mails. [15]

American Philosophical Society (1743)

In 1743 Benjamin Franklin and his friend the Quaker botanist John Bartram (1699-1777) established the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia as a declaration of scientific independence from Great Britain’s scientific domination. Brooke Sylvia Palmieri states in her web article ” The APS developed from a group of local intellectuals keen on expanding human knowledge to serve informally as the national academy of science and national library for a half century after 1790, when the United States capital moved to Philadelphia.”

Palmieri continues, “Franklin and Bartram organized the APS to promote advancement in all fields of science. They proposed that there should be no fewer than seven members: a physician, botanist, mathematician, chemist, mechanic, geographer, and natural philosopher, in addition to a president, treasurer, and secretary. Members would meet once a month to conduct experiments in brewing, navigation, and agriculture among other subjects.” [16]

Daughter Sally was born (1743)

Sarah “Sally” Franklin was born on September 11, 1743. She would be the only surviving child of Benjamin and Deborah Reed. Growing up Benjamin did not have a close relationship with Sally and this relationship would stay strained throughout his lifetime. For instance, Sally isn’t even mentioned in his autobiography. But towards the end of his life he chose to live with Sally and her family and she helped care for him. When Benjamin died, he left the bulk of his estate to her and her husband. [17]

Benjamin Fly's a Kite (1752)

In Philadelphia in June of 1752, trying to demnstrate the electrical nature of lightning, he decided to take his son William out to a field and fly a kite. He grabbed his materials as stated in The Franklin Institute article “a simple kite made with a large silk handkerchief, a hemp string, and a silk string. He also had a house key, a Leyden jar (a device that could store an electrical charge for later use), and a sharp length of wire. Despite a common misconception, Benjamin Franklin did not discover electricity during this experiment—or at all, for that matter. Electrical forces had been recognized for more than a thousand years, and scientists had worked extensively with static electricity. Franklin’s experiment demonstrated the connection between lightning and electricity.” For more details please see the article here [18]

Since 1746 Franklin had been intriqued by electricity after meeting Dr. Spence of Scotland. Franklin had done many electrical experiments and sent several letters about the experiments to Peter Collison from the Royal Society of London.[19]

Appointed Joint Deputy Postmaster General of North America (1753)

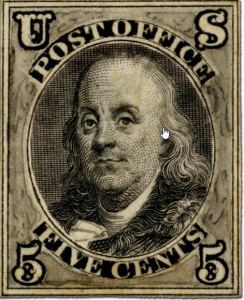

Benjamin Franklin Stamp Franklin 5-cent stamp Smithsonian Postal Museum

USPS Historian writes “While Franklin was already Deputy Postmaster General, Postmaster General Elliott Benger (1743-1753) added to Franklin’s duties by making him comptroller with financial oversight over neighboring Post Offices. When Benger’s health failed, Franklin lobbied the British for the job of postmaster general of America. On August 10, 1753, he and William Hunter of Virginia became joint postmasters general for the Crown.”

The historian continues: “As joint postmaster general, Franklin surveyed post roads and Post Offices, introduced a simple accounting method for postmasters, and had riders carry mail by night as well as day, speeding service. He encouraged postmasters to establish the penny post, a British idea he had implemented while postmaster of Philadelphia, whereby letters not called for at the Post Office were delivered for a penny. He also ordered postmasters to print in newspapers the names of people who had letters waiting for them. Remembering his own experiences as a printer and postmaster, Franklin abolished the practice of letting postmasters decide which newspapers could travel through the mail and mandated delivery of all newspapers for a small fee. Thanks in part to Franklin’s efforts, the British Crown Post in North America registered its first profit in 1760.” For more information please click here [20]

Goes to London as an agent of Pennsylvania (1757-1762)

As Joan Paterson Kerr writes ” Franklin had been appointed as an agent (in effect, a lobbyist) by the Provincial Assembly of Pennsylvania to represent its interests against the brothers Penn, sons of William, the founder of the colony of Pennsylvania, and in their own view the ‘True and Absolute Proprietors’ of the original royal charter of 1681, with all the rights and privileges appertaining thereto. Among those rights and privileges, the brothers Penn maintained, was that their own extensive landholdings should not be taxed at the same level as those of the common folk. The assembly disagreed, and Franklin’s mission in London was to persuade British officialdom that the assembly was right.”[21]

With this, Franklin suddenly emerged as the leading spokesman for American interests in England. He wrote popular essays on behalf of the colonies. Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts also appointed him as their agent to the Crown [22]

Begins to write his Autobiography (1771-1772)

Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography is both an important historical document and Franklin’s major literary work. It was not only the first autobiography to achieve widespread popularity, but after two hundred years remains one of the most enduringly popular examples of the genre ever written. The autobiography was written from 1771 – 1790.

Ben's wife Deborah dies (1774)

Franklin’s wife, Deborah Reed dies on December 19 in Philadelphia at age 44. Womenhistoryblog writes: ” Around 1773, Deborah began experiencing health problems. Franklin was in England, trying to keep peace between America and England, and he was unable to return to the colonies. In 1774, he wrote her a letter in which, for the first time, he used the tender term “my dear Love,” but she was too ill to respond or even acknowledge it. Her fear of ocean voyages had prevented Debprah from traveling with her husband, so she spent many years alone. She died unexpectedly of a stroke on December 19, 1774 in Philadelphia, while Franklin was in England.” [23]

Appointed as a Delegate to the 2nd Continental Congress (1775)

Benjamin Franklin returned from London in May, 1775, and was quickly drafted as one of the Pennsylvania delegates to the second Continental Congress. Franklin’s plan for a government for a united colonial confederation was read in Congress on July 21, 1775, but was not acted upon at that time. [24]

Appointed Postmaster General of the Colonies (1775)

On July 26, 1775, the Congress appointed Benjamin Franklin the first Postmaster General of the organization now known as the United States Postal Service. Franklin received an annual salary of $1,000 plus $340 for a secretary and comptroller. He was responsible for all Post Offices — from Massachusetts to Georgia — and had authority to hire as many postmasters as he saw fit. [25]

Helps write the Declaration of Independence (1776)

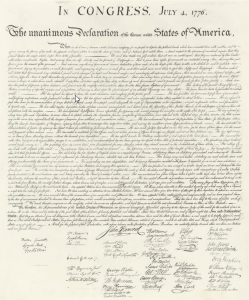

Franklin was selected to be on the 5 person committee to draft the Declaration of Indepence. The Franklin Institute writes “Benjamin Franklin primarily served as the editor of the Declaration of Independence. His changes were believed to have been minimal, but, when the document went before the entire Continental Congress, the draft was more thoroughly changed by the larger body from Jefferson’s original text. The final document was passed on July 2, 1776 and ratified on July 4, 1776.” [26]

Franklin was selected to be on the 5 person committee to draft the Declaration of Indepence. The Franklin Institute writes “Benjamin Franklin primarily served as the editor of the Declaration of Independence. His changes were believed to have been minimal, but, when the document went before the entire Continental Congress, the draft was more thoroughly changed by the larger body from Jefferson’s original text. The final document was passed on July 2, 1776 and ratified on July 4, 1776.” [26]

Goes to Paris (1776)

Wikipedia writes “In December 1776, Franklin was dispatched to France as commissioner for the United States. He took with him as secretary his 16-year-old grandson, William Temple Franklin. Franklin remained in France until 1785. He conducted the affairs of his country toward the French nation with great success, which included securing a critical military alliance in 1778 and negotiating the Treaty of Paris (1783).” [27]

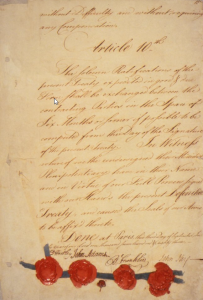

The Treaty of Alliance (1778)

The Treaty of Alliance and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce were signed on February 6, 1778. The Treaty called for mutual defense in case France or the Union was attacked by the British. One of the clauses in the treaty specified that neither country could seek a separate peace agreement with Britain. Once the treaty was signed Spain joined the war. This alliance was one of Franklin’s most important achievements which led to French military aid, fundamental in the fight against Britain. [28]

Peach Treaty in Paris(1778)

In 1778, the Continental Congress appointed Franklin, John Adams and John Jay to go to Paris to negotiate an end to the war. The rule of King George III ended and the new ministry included old friends of the Americans who were prepared to negotiate a peace settlement with America.

In 1778, the Continental Congress appointed Franklin, John Adams and John Jay to go to Paris to negotiate an end to the war. The rule of King George III ended and the new ministry included old friends of the Americans who were prepared to negotiate a peace settlement with America.

In November 1782, Jay and Franklin agreed to separate peace talks with the British, which produced a preliminary treaty with Great Britain. Britain agreed to the treaty terms because the American representatives played on existing rivalries among the European powers. [29]

Invents Bifocals (1784)

In 1784, as Franklin aged his vision got much worse. He was wanting to be able to see long distances and still have the ability to read, which was his favorite thing to do. So he invented what he called “double-spectacles.” Franklin wrote to his optician and made a request: take both his long distance glasses and his reading glasses, slice their lenses in half and then suture the lenses together with the reading lenses on the bottom and the long distance glasses on the top. [30]

Signs the Constitution (1787)

In September 1787, the Constitution was completed, but many delegates were not in agreement. As written at PBS.org “Franklin wrote an impassioned speech, in which he used his persuasive powers to urge all delegates to sign the Constitution. Franklin admitted that it was an imperfect document but probably the best they could expect. Following the speech, the Constitution was signed. To Franklin’s disappointment, some delegates still refused to sign.” [31] More Details

Death (1790)

Benjamin Franklin died from pleuritic attack at his home in Philadelphia on April 17, 1790. He was aged 84 at the time of his death. His last words were reportedly, “a dying man can do nothing easy”, to his daughter after she suggested that he change position in bed and lie on his side so he could breathe more easily. [32]. More details from the Benjamin Franklin Historical Society.

References

- 1. benjamin-franklin-history.org/junto-club

- 2. William Franklin - Wikepedia

- 3. Pennsylvania Gazette

- 4. Pennsylvania Gazette

“The Pennsylvania Gazette,” The News Media and the Making of America, 1730-1865, https://www.americanantiquarian.org/earlyamericannewsmedia/items/show/110. - 5. accessible-archives.com

- 6. Wikipedia - Deborah Read

- 7. www.benjamin-franklin-history.org/marriage-and-children

- 8. The Library_Company_of_Philadelphia

- 9. benjamin-franklin-history.org/lending-library

- 10. Document shows evidence of first U.S. franchise, first female franchisee; September 08, 2007 By Hilary Strahota

- 11. benjamin-franklin-history.org/franchise-and-retirement-from-printing/

- 12. legis.state.pa.us - House of Speaker Biographies - Benjamin-Franklin

- 13. UShistory.org Benjamin Franklin - In Case of Fire

- 14. Benjamin Franklin: Philadelphia’s Postmaster 06.06.2017, Blog By Nancy Pope, Historian and Curator

- 15. Mychimney.com - Franklin Stove

- 16. American Philosophical Society By Brooke Sylvia Palmieri Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

- 17. Sarah Franklin Bache Wikipedia

- 18. Benjamin Franklin and the Kite Experiment by By Nancy Gupton. Published June 12, 2017 The Franklin Institue

- 19. Experiments with electricity - Benjamin Franklin Historical Society

- 20. HISTORIAN UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE FEBRUARY 2003 - USPS

- 21. Benjamin Franklin’s Years In London by Joan Paterson Kerr December 1976 - Volume 28, Issue 1

- 22. Benjamin Franklin Wikipedia Wikipedia

- 23. Deborah Reed Franklin HISTORY OF AMERICAN WOMEN

- 24. Library of Congress - Benjamin

- 25. USPS Postal History

- 26. The Franklin Institute

- 27. Wikipedia - Benjamin Franklin Ambassador to France

- 28. Benjamin-Franklin-history.org Alliance with France

- 29. Peace Treaty phoenix.k12.or.us

- 30. Benjamin Franklin Bifocals by Michael Benton

- 31. Benjamin Franklin - Founding Father - PBS PBS.org

- 32. Benjamin Franklin - Wikipedia Wikepdia.com